Summary

Psychology of Money Chapter wise In depth Summary: 19 Lessons on Wealth & Happiness

1: No One’s Crazy

“Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.”

What people do with money often looks irrational. But when you understand their past, it almost always makes sense.

Chapter Summary

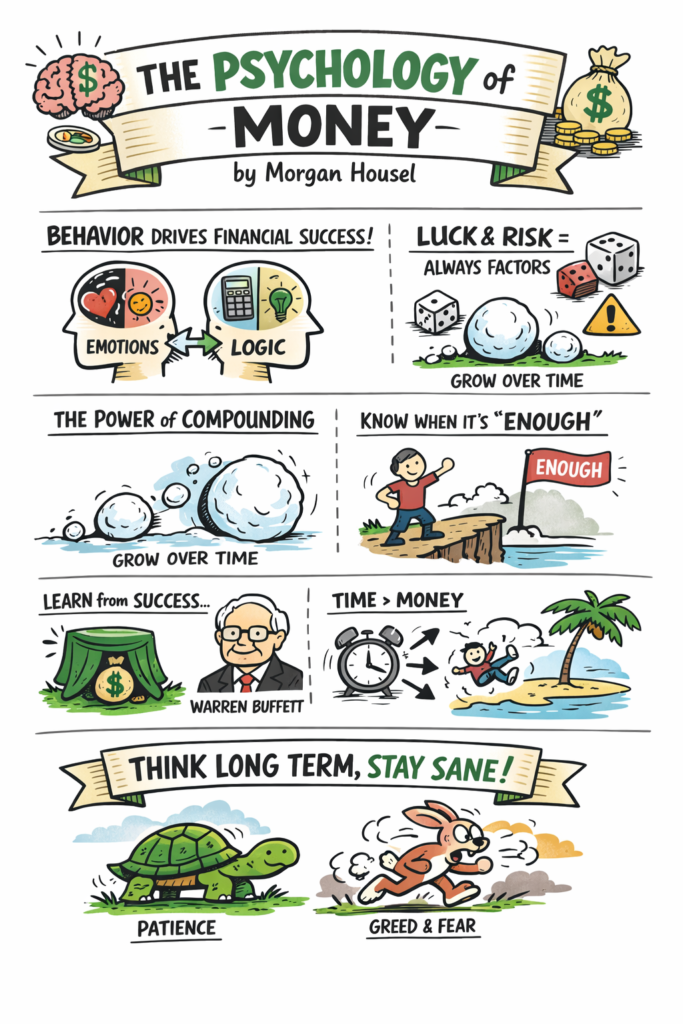

Money Decisions Are Shaped by Life, Not Logic

This chapter opens with a simple but powerful idea: people are not crazy with money. They behave in ways that feel reasonable to them based on what they have lived through. Money decisions are rarely made in spreadsheets or textbooks. They are made at dinner tables, during job losses, in moments of fear, and in times of optimism. Experiences like growing up poor, living through inflation, witnessing a market crash, or enjoying long periods of stability leave deep emotional marks that influence how people think about risk and safety.

Someone who lived through the Great Depression may fear stocks for life. Someone who only saw rising markets may believe downturns are temporary and harmless. Neither person is stupid. They are responding to the strongest teacher of all: personal experience.

Why Smart People Disagree About Money

Housel explains why two equally intelligent people can strongly disagree on financial decisions. It is not because one is better informed. It is because they have seen different versions of the world. A person raised during high inflation thinks about money differently from someone who grew up when prices were stable. A worker who lost everything in a recession approaches debt cautiously, while someone who never experienced job loss may feel comfortable borrowing aggressively.

The key insight is that what feels safe or risky is not universal. It is learned. This explains why financial debates are often emotional and personal. People are defending not just opinions, but memories.

Why Most Financial Advice Fails

Most financial advice assumes people start from the same place. They don’t. Advice like “invest aggressively” or “take more risk when you’re young” ignores personal fears, responsibilities, and past trauma. What worked for one person may be dangerous for another.

Housel argues that good financial decisions are not about finding the “correct” strategy. They are about finding a strategy you can stick with during stress, uncertainty, and fear. A plan that looks perfect on paper but causes panic in real life is a bad plan.

Understanding this helps you stop copying others blindly and start designing decisions that fit your own reality.

Why should the reader care?

Because copying money advice without considering your own life can lead to regret and avoidable mistakes.

Mental Model

Money behavior follows lived experience, not intelligence.

Key Insights

- People make money decisions based on what they’ve personally experienced

- Financial disagreements often come from different life histories, not ignorance

- Intelligence does not protect against poor money behavior

- The best financial plan is one that fits your emotional reality

Common Mistake to Avoid

Judging your own or others’ financial decisions as “wrong” without understanding the experiences behind them.

A Better Way to Think About Money Decisions (Practical Principle)

Instead of asking, “Is this the smartest move?”, ask:

“Can I live with this decision if things go wrong?”

Durability matters more than brilliance.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Write down three money beliefs you strongly hold and trace where they came from

- Stop comparing your financial strategy with people who lived very different lives

- Choose financial plans you can stick with during fear, not just optimism

- Replace judgment (of yourself and others) with curiosity

Chapter in One Sentence

People aren’t bad with money—they’re shaped by different experiences.

2: Luck & Risk

“Nothing is as good or as bad as it seems.”

Success and failure look clean in hindsight. In real life, they are tangled with chance.

Chapter Summary

Success Is a Combination of Skill and Chance

This chapter challenges one of the most comforting beliefs people hold: that success is mostly earned through talent and effort. Morgan Housel argues that while hard work matters, luck plays a far greater role in outcomes than most people are willing to admit. Timing, opportunity, and circumstances outside personal control quietly shape results.

To explain this, Housel tells the story of Bill Gates. Gates was brilliant and hardworking, but he also attended one of the very few schools in the world that had a computer at the exact moment computers were becoming revolutionary. That access—pure luck—gave him a massive head start. Gates himself openly admits this. Talent mattered, but timing mattered just as much.

Why Risk Is the Invisible Twin of Luck

Luck and risk are inseparable. If good fortune can push someone forward, bad fortune can pull someone down with equal force. For every success story shaped by lucky breaks, there are equally capable people who experienced unlucky events—illness, accidents, economic crashes—that erased their progress.

Housel illustrates this through Bill Gates’ childhood friend, Kent Evans, who was just as talented but died in a tragic accident. Same skill, same ambition, completely different outcome. This contrast reveals an uncomfortable truth: effort does not guarantee results.

Why We Learn the Wrong Lessons

Humans naturally study winners and copy them. But this is dangerous. We rarely see the role of luck behind success, and we often blame failure entirely on poor decisions. This creates overconfidence during good times and unnecessary shame during bad ones.

The lesson is not to dismiss effort—but to treat outcomes with humility.

Why should the reader care?

Because confusing luck for skill can push you into risks that ruin long-term stability.

Mental Model

Outcomes are shaped by effort, filtered through randomness.

Key Insights

- Luck plays a larger role in success than most people admit

- Risk affects outcomes just as powerfully as skill

- Failure does not always mean bad decisions

- Judging results without context leads to false lessons

Common Mistake to Avoid

Assuming that successful people fully deserve their outcomes—and unsuccessful people fully caused theirs.

A Smarter Way to Judge Money Decisions (Practical Principle)

Judge decisions by their process, not their outcome. Ask whether a choice was reasonable given the information available at the time, not whether it “worked.”

This mindset encourages better long-term behavior and reduces emotional overreaction.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Study both success stories and failures before drawing conclusions

- Build margin of safety into financial decisions to absorb bad luck

- Stay humble during wins and forgiving during losses

- Avoid extreme confidence after short-term success

Chapter in One Sentence

Luck and risk shape outcomes far more than we realize, so humility is essential.

3: Never Enough

“The hardest financial skill is getting the goalpost to stop moving.”

There is a moment when more money stops improving life—and starts increasing risk.

Chapter Summary

When Ambition Quietly Turns Into Danger

This chapter explores one of the most destructive money mindsets: the inability to recognize when you have enough. Housel shows that many financial failures do not happen because people lack money, but because they already have plenty and still push further. The desire for more—more wealth, more status, more recognition—can quietly shift behavior from sensible to reckless.

Housel uses real-life examples of extremely wealthy individuals who lost everything, not because they were poor decision-makers early on, but because they continued to take risks long after their basic needs, comfort, and security were met. At that point, the upside was marginal, but the downside was catastrophic.

The Trap of Social Comparison

A major reason “enough” feels invisible is comparison. No matter how much wealth you accumulate, there will always be someone richer. When success is measured relative to others instead of personal needs, satisfaction disappears. Comparison turns progress into pressure and makes restraint feel like failure.

This explains why even very successful people feel dissatisfied. They are not chasing comfort—they are chasing position.

Why Expectations Control Happiness

Housel introduces a powerful idea: happiness equals results minus expectations. When expectations rise faster than results, frustration is guaranteed. Knowing when to stop is not a lack of ambition; it is a survival skill that protects freedom, reputation, and peace of mind.

Why should the reader care?

Because chasing more than you need can quietly destroy everything you already have.

Mental Model

More becomes risk when expectations never stop rising.

Key Insights

- Many financial disasters happen after people are already successful

- Social comparison makes “enough” impossible to see

- Satisfaction depends on expectations, not absolute wealth

- Protecting what you have matters more than chasing marginal gains

Common Mistake to Avoid

Risking essential things—freedom, reputation, family, or peace of mind—for money you no longer need.

Guardrails That Protect Long-Term Wealth (Practical Principle)

Some things should never be put at risk for financial gain. Once basic needs and independence are secured, the goal shifts from growth to preservation. Survival beats ambition at this stage.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Clearly define what “enough” means for your lifestyle and goals

- Stop measuring success using other people’s benchmarks

- Identify risks you will never take, regardless of reward

- Shift focus from maximum growth to long-term sustainability

Chapter in One Sentence

Wealth lasts when you know when to stop.

Reflection:

Money & Perspective

Question:

How have your personal experiences shaped the way you think about money, risk, and success?

Why it matters:

Awareness of your past helps you avoid copying strategies that don’t fit your reality.

4: Confounding Compounding

“Good investing isn’t necessarily about making good decisions. It’s about consistently not screwing up.”

Compounding is simple to explain, but incredibly hard to live through.

Chapter Summary

Why Compounding Feels Disappointing at First

Compounding is one of the most powerful forces in finance, yet it is widely misunderstood because it works slowly and unevenly. In the early stages, progress feels small, boring, and almost meaningless. Returns don’t appear impressive, which leads many people to abandon the process before its real power shows up. This impatience causes people to chase new strategies, switch investments, or give up entirely—right before compounding would have started doing the heavy lifting.

Housel emphasizes that compounding does not reward intensity or brilliance. It rewards time and endurance. The hardest part is staying invested during long periods when nothing exciting seems to be happening.

Time Is the Real Competitive Advantage

The chapter uses Warren Buffett as a powerful example. Buffett is often praised for his intelligence, but Housel points out that Buffett’s biggest advantage is longevity. He started investing very young and continued for decades. Most of his wealth was created later in life, not because he suddenly became smarter, but because compounding had more time to work.

This reframes success: extraordinary results often come from ordinary decisions repeated patiently over long periods.

Why Survival Matters More Than Big Wins

Compounding only works if you stay in the game. One major mistake—panic selling, excessive leverage, or chasing risky shortcuts—can erase years of progress. Avoiding failure is just as important as earning returns.

Why should the reader care?

Because impatience can destroy the most powerful advantage money gives you.

Mental Model

Time multiplies ordinary decisions into extraordinary outcomes.

Key Insights

- Compounding feels weak before it becomes powerful

- Time matters more than talent or intelligence

- Most wealth is created late, not early

- Big mistakes can undo years of progress

Common Mistake to Avoid

Abandoning long-term strategies because early results feel slow or unimpressive.

Staying in the Game Is the Strategy (Practical Principle)

The goal is not to maximize short-term returns. The goal is to survive long enough for compounding to work. Durability beats brilliance.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Start early, even if the amount feels small

- Avoid strategies that risk wiping you out completely

- Stay consistent during boring or slow periods

- Focus on long-term behavior, not short-term performance

Chapter in One Sentence

Wealth grows when patience outlasts impatience.

5: Getting Wealthy vs. Staying Wealthy

“Getting money requires taking risks, being optimistic, and putting yourself out there. Staying wealthy requires the opposite.”

Getting rich is exciting. Staying rich is quiet, defensive, and far more difficult.

Chapter Summary

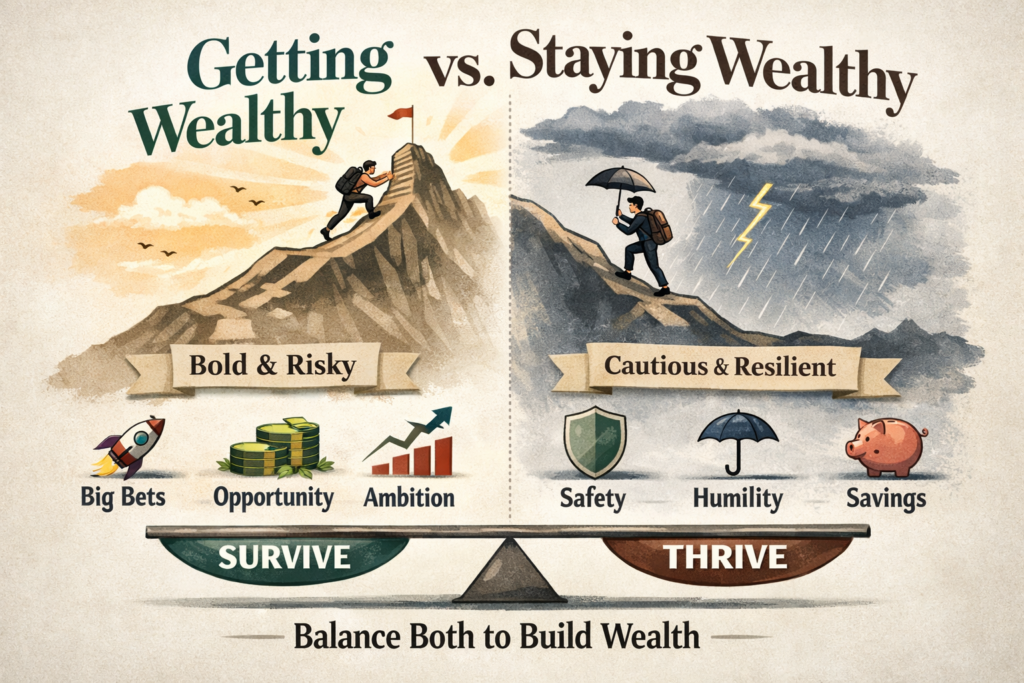

Getting Wealthy Rewards Boldness and Optimism

Housel begins by explaining that building wealth often requires risk-taking. People who get wealthy usually believe the future will be better than the present. They are willing to invest, borrow, start businesses, and expose themselves to uncertainty. Optimism is rewarded in growing economies, rising markets, and periods of innovation.

This phase of wealth-building celebrates courage and confidence. Risk is framed as opportunity, and volatility is accepted as the cost of progress. Many people associate this stage with success stories because it looks dynamic and impressive.

Staying Wealthy Is a Different Game Entirely

Staying wealthy, however, requires a complete shift in mindset. Once wealth is built, the goal is no longer aggressive growth—it is survival. The biggest threat at this stage is not low returns but ruin. A single catastrophic decision can erase decades of effort.

Housel emphasizes that many people fail because they continue to play offense when they should be playing defense. They assume the same behaviors that helped them win will help them keep winning. Often, they don’t.

The Power of Endurance Over Brilliance

Long-term financial success belongs to those who avoid being wiped out. Survival allows compounding to continue. Endurance, not intelligence, becomes the most important skill. Staying wealthy means managing risk, reducing exposure to failure, and maintaining flexibility—even if it means accepting lower returns.

Why should the reader care?

Because one reckless decision can undo a lifetime of disciplined effort.

Mental Model

In a game with no finish line, survival is the only real victory.

Key Insights

- Getting wealthy and staying wealthy require opposite behaviors

- Risk-taking builds wealth, but risk control preserves it

- Avoiding ruin matters more than maximizing returns

- Longevity is the most underrated financial advantage

Common Mistake to Avoid

Using aggressive, high-risk strategies to protect wealth instead of to build it.

Playing Defense Is the Real Strategy (Practical Principle)

Once basic security and independence are achieved, the goal shifts from growth to durability. Low debt, flexibility, and room for error protect long-term freedom.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Reduce financial leverage that could cause permanent loss

- Build buffers for unexpected downturns

- Accept lower returns in exchange for stability

- Choose strategies you can survive during bad years

Chapter in One Sentence

Getting wealthy requires risk; staying wealthy requires avoiding ruin.

6: Tails, You Win

“A small number of events can account for the majority of outcomes.”

Most outcomes in life and investing are driven by a few moments that matter far more than everything else combined.

Chapter Summary

Why Results Are Never Evenly Distributed

This chapter explains a reality that feels unfair but is deeply important: success does not come from consistent small wins. It comes from a few rare events that dominate results. In investing, business, and careers, most actions produce average or poor outcomes, while a small number of decisions create extraordinary impact.

Housel shows that this pattern exists everywhere. A handful of companies drive most stock market returns. A few inventions shape entire industries. A small number of career choices define lifetime success. This uneven distribution is not a flaw—it is how the world works.

Missing Big Wins Matters More Than Small Losses

Because results are concentrated, avoiding every small loss is less important than staying exposed to the possibility of a big win. Many people fail not because they make too many mistakes, but because they quit early, become overly cautious, or abandon strategies after short-term disappointment.

The challenge is that you never know in advance which decision will be the one that matters most. Big wins often look ordinary or risky at the start.

Staying in the Game Is the Only Reliable Strategy

Since you cannot predict which moments will define success, the best strategy is endurance. Those who remain patient through boredom, setbacks, and small failures give themselves the highest chance of being present when rare opportunities appear.

Why should the reader care?

Because quitting early almost guarantees you will miss the outcomes that matter most.

Mental Model

A few big wins outweigh many small losses.

Key Insights

- Most results come from a small number of events

- Many efforts will fail, and that is normal

- Big wins are rare and unpredictable

- Staying invested increases exposure to success

Common Mistake to Avoid

Expecting every decision to work instead of allowing for uneven outcomes.

Positioning Yourself for Rare Wins (Practical Principle)

Accept frequent small failures as the cost of staying exposed to rare, powerful opportunities. Avoid strategies that force you to quit before those opportunities appear.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Avoid approaches that punish you for short-term losses

- Judge progress over long periods, not short streaks

- Stay diversified to increase exposure to upside

- Remain patient during slow or uneven progress

Chapter in One Sentence

Most success comes from a few rare wins, so staying in the game matters more than being right often.

7: Freedom

“The ability to do what you want, when you want, with who you want, for as long as you want, is priceless.”

Money is not about buying things. It is about buying control over your life.

Chapter Summary

The Highest Return Money Can Give

This chapter reframes the purpose of wealth. Most people think money is meant to buy comfort, luxury, or status. Housel argues that its greatest value is freedom—the ability to control your time. Being able to choose when you work, when you rest, and what you focus on brings a deeper and more lasting form of happiness than material possessions.

Freedom means not being forced into decisions by bills, bosses, or fear. It creates space to walk away from bad jobs, unhealthy relationships, or stressful obligations. This kind of control quietly reduces anxiety and increases satisfaction.

Why Status Spending Steals Freedom

Many people trade freedom for status without realizing it. They increase expenses to look successful, locking themselves into jobs and lifestyles they cannot escape. The cost is not just money—it is time, flexibility, and peace of mind.

Housel highlights that people who value freedom often live below their means. They sacrifice visible success for invisible independence.

Flexibility Is Emotional Insurance

When you control your time, you reduce dependence on markets, employers, and other people’s expectations. This flexibility becomes a powerful form of insurance during uncertainty, economic downturns, or personal change.

Why should the reader care?

Because freedom—not possessions—is what makes money meaningful.

Mental Model

Money’s greatest return is control over time.

Key Insights

- Time control is more valuable than luxury

- Spending less increases independence

- Status often trades freedom for approval

- Flexibility reduces stress and regret

Common Mistake to Avoid

Using money primarily to impress others instead of to gain control over your life.

Designing a Freedom-First Life (Practical Principle)

Prioritize financial decisions that increase flexibility: low fixed costs, fewer obligations, and the ability to say no when needed.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Reduce recurring expenses that lock you into stress

- Save with the goal of flexibility, not status

- Choose work that offers autonomy when possible

- Measure wealth by time freedom, not appearances

Chapter in One Sentence

The true purpose of money is to buy control over your time.

8: Man in the Car Paradox

“No one is impressed with your possessions as much as you think.”

When people admire expensive things, they are usually admiring themselves in your place—not you.

Chapter Summary

We Don’t Admire Objects, We Admire Status

This chapter explains a subtle psychological illusion. When you see someone driving a luxury car or living an extravagant lifestyle, you may feel admiration. But that admiration is rarely about the object itself. Instead, you imagine what it would feel like to be the person who owns it—respected, successful, admired.

Housel calls this the “Man in the Car Paradox.” The owner thinks others are impressed by the car. In reality, observers are picturing themselves in the driver’s seat. The object becomes a prop in someone else’s fantasy, not a source of real admiration for the buyer.

Why Status Spending Fails to Deliver

Many people spend money to gain respect or validation. But the attention they seek never arrives. Observers don’t think about the buyer’s sacrifices, debt, or stress. They move on quickly, leaving the buyer with fewer resources and less freedom.

The paradox is painful: the person who pays the price gets the least benefit.

Invisible Wealth Creates Real Confidence

True confidence does not come from being seen as rich. It comes from financial security, flexibility, and peace of mind—things that are invisible. The most financially secure people often appear ordinary because they prioritize independence over attention.

Why should the reader care?

Because spending to impress others rarely earns admiration—and often costs freedom.

Mental Model

Status is imagined; freedom is real.

Key Insights

- People admire status, not possessions

- Observers focus on themselves, not the buyer

- Status spending benefits others more than you

- Invisible wealth creates lasting security

Common Mistake to Avoid

Buying expensive things to gain respect or approval from others.

Redefining What Success Looks Like (Practical Principle)

Use money to improve your life, not to signal your worth. Independence and peace of mind are better measures of success than attention.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Pause before major purchases and ask who it’s really for

- Spend less on visibility and more on flexibility

- Measure success by stress reduction, not admiration

- Build wealth quietly rather than publicly

Chapter in One Sentence

Spending to impress others rarely impresses anyone—and often costs your freedom.

9: Wealth Is What You Don’t See

“Wealth is what you don’t see.”

The most important part of wealth is invisible—and that is why it is so often misunderstood.

Chapter Summary

Why Spending and Wealth Are Opposites

This chapter dismantles a common misconception: that wealth is defined by what people buy. Housel explains that spending money is the opposite of being wealthy. When you spend, you are turning future options into present consumption. True wealth, on the other hand, is the money you save—the money you didn’t spend.

People often assume that someone living an expensive lifestyle must be rich. In reality, that lifestyle may be supported by debt, stress, and fragile finances. Meanwhile, someone living modestly may have significant savings, investments, and flexibility that are completely invisible to outsiders.

The Quiet Power of Financial Slack

Wealth creates comfort not through display, but through optionality. Having money saved means you can handle emergencies, walk away from bad situations, and make decisions without desperation. This “slack” in the system reduces stress and increases confidence—even though no one else can see it.

Housel emphasizes that this invisible buffer is what actually makes people feel secure. It’s not the car in the driveway, but the freedom behind the scenes.

Why Visibility Misleads Us

Humans are wired to judge by what they can see. This causes us to confuse consumption with success and saving with scarcity. Over time, this misunderstanding leads people to prioritize appearance over resilience.

Why should the reader care?

Because confusing spending with wealth can trap you in a lifestyle that looks successful but feels fragile.

Mental Model

Spending is visible; wealth is invisible.

Key Insights

- Wealth is the money you don’t spend

- High spending often hides financial fragility

- Savings create flexibility and peace of mind

- True security is quiet, not flashy

Common Mistake to Avoid

Assuming that visible success equals financial strength.

Building Invisible Strength (Practical Principle)

Prioritize saving and flexibility over appearance. The goal of money is not to look rich, but to be secure.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Track savings growth, not lifestyle upgrades

- Avoid lifestyle inflation when income increases

- Build financial buffers before buying luxuries

- Measure progress by flexibility, not display

Chapter in One Sentence

Real wealth is the money you choose not to spend.

10: Save Money

“Building wealth has little to do with your income or investment returns, and lots to do with your savings rate.”

Saving money is not about being rich. It is about controlling your behavior.

Chapter Summary

Saving Is a Habit, Not a Number

This chapter challenges the belief that saving depends on earning more. Housel explains that wealth is built by the gap between what you earn and what you spend—not by income alone. People with high salaries who spend everything are often less secure than modest earners who save consistently. Saving is a behavioral skill, not a financial calculation.

The act of saving itself matters more than the amount. Even small savings, done regularly, build discipline and resilience. Over time, this habit compounds into real financial strength.

Saving Creates Independence

Housel reframes saving as a way to buy freedom. Money saved gives you control over your choices—where you work, when you stop, and how you respond to uncertainty. This flexibility is more valuable than any short-term return from spending.

Saving also protects you from relying on perfect outcomes. You don’t need every plan to work if you have a buffer.

Control What You Can Control

Investment returns are unpredictable. Spending is not. Focusing on savings gives you control in a world full of uncertainty.

Why should the reader care?

Because saving gives you power even when income or markets are uncertain.

Mental Model

Savings buy independence, not deprivation.

Key Insights

- Saving matters more than income level

- Wealth comes from the gap between earning and spending

- Small, consistent savings create long-term strength

- Control beats prediction

Common Mistake to Avoid

Waiting to save until you earn “enough” money.

Saving as a Strategic Advantage (Practical Principle)

Treat saving as a permanent habit, not a temporary phase. The goal is flexibility, not sacrifice.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Automate savings before spending

- Increase savings when income rises

- Reduce fixed expenses that limit flexibility

- Focus on consistency, not perfection

Chapter in One Sentence

Saving is the foundation of freedom, regardless of income.

11: Reasonable > Rational

“Do not aim to be coldly rational when making financial decisions. Aim to be reasonable.”

The best financial strategy is useless if you can’t stick with it.

Chapter Summary

Why Perfect Logic Often Fails in Real Life

This chapter challenges the idea that the best financial decisions are always the most mathematically optimal ones. Housel argues that humans are not robots. We experience fear, stress, doubt, and regret. A strategy that looks perfect on paper can fall apart when emotions enter the picture.

Being fully “rational” might mean staying invested through extreme volatility or maximizing returns at the cost of sleepless nights. But if a plan causes panic or anxiety, people eventually abandon it—often at the worst possible time. A broken plan, no matter how smart, is worse than a slightly less optimal plan that you can follow consistently.

Why Reasonable Decisions Win Over Time

Reasonable decisions account for human behavior. They prioritize comfort, clarity, and peace of mind. A reasonable investor might accept lower returns in exchange for stability. That trade-off often leads to better long-term results because the investor stays disciplined during stress.

Housel’s key insight is simple: the best financial behavior is the one you can maintain for decades.

Consistency Beats Optimization

Long-term success comes from sticking with a plan, not constantly improving it. Being reasonable helps you stay invested, stay calm, and avoid emotional mistakes.

Why should the reader care?

Because a strategy you can’t emotionally handle will eventually fail.

Mental Model

Consistency beats mathematical perfection.

Key Insights

- Humans are emotional, not purely logical

- Rational plans fail when emotions take over

- Reasonable strategies are easier to stick with

- Long-term consistency matters more than optimization

Common Mistake to Avoid

Choosing a “perfect” financial plan that causes stress, fear, or panic during downturns.

Designing a Plan You Can Live With (Practical Principle)

Build financial strategies that match your emotional tolerance. A slightly less aggressive plan you can follow is better than a perfect plan you abandon.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Choose investments that let you sleep at night

- Simplify strategies that feel overwhelming

- Accept lower returns in exchange for peace of mind

- Measure success by discipline, not maximum gains

Chapter in One Sentence

The best financial strategy is the one you can stick with for life.

12: Surprise!

“History is driven by surprising events.”

The future will not look like the past—and that’s exactly what makes it dangerous to predict.

Chapter Summary

Why the Biggest Events Are Always Unexpected

This chapter focuses on a simple but uncomfortable truth: the most important events in history are rarely predicted. Wars, recessions, technological breakthroughs, market crashes, and booms often come from places no one expects. Yet, most planning assumes the future will behave like the past.

Housel explains that humans are drawn to neat explanations and forecasts. We study patterns, build models, and create narratives that make the world feel predictable. But history shows that a small number of unexpected events shape outcomes far more than gradual trends.

Why Forecasting Creates False Confidence

Forecasts give the illusion of control. They make us feel prepared, even when they are based on limited data and fragile assumptions. When people believe they understand what will happen next, they often take bigger risks—just before reality proves them wrong.

Housel argues that this overconfidence is more dangerous than uncertainty itself. Believing the future is predictable leads people to ignore the possibility of shock.

Preparing for Surprise Instead of Predicting It

The lesson is not to stop thinking about the future, but to stop pretending it can be forecast precisely. Planning should focus on resilience—having the flexibility and buffers to survive outcomes that no one saw coming.

Why should the reader care?

Because surprises, not predictions, shape the most important outcomes.

Mental Model

Uncertainty is normal; surprise is inevitable.

Key Insights

- The most impactful events are rarely predicted

- Forecasts often create false confidence

- History is shaped by shocks, not smooth trends

- Preparing for surprise is wiser than predicting the future

Common Mistake to Avoid

Relying heavily on forecasts and models while ignoring the possibility of unexpected events.

Planning for an Uncertain World (Practical Principle)

Instead of asking, “What will happen next?” ask, “How would I cope if I’m wrong?” Build plans that survive uncertainty.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Build financial buffers instead of perfect forecasts

- Avoid strategies that fail under surprise scenarios

- Stay flexible rather than overcommitted

- Expect the unexpected in long-term planning

Chapter in One Sentence

The future is shaped by surprises, so resilience matters more than prediction.

13: Room for Error

“The most important part of every plan is planning for when the plan doesn’t go according to plan.”

The difference between success and failure is often how much room you leave for things to go wrong.

Chapter Summary

Why Perfect Plans Fail

This chapter focuses on a principle that quietly determines long-term success: room for error. Housel explains that no plan—financial or otherwise—works exactly as expected. Markets fall, income changes, health issues arise, and mistakes happen. Plans that assume perfect execution collapse when reality intervenes.

Many people design financial strategies that work only if everything goes right. These plans leave no margin for error. When even a small setback occurs, they are forced into desperate decisions, often at the worst possible time.

Safety Margins Keep You in the Game

Room for error acts as a shock absorber. Extra savings, lower debt, and conservative assumptions give you the ability to survive bad luck without panic. This margin does not eliminate risk, but it prevents small problems from becoming permanent failures.

Housel emphasizes that success is often less about making brilliant choices and more about avoiding fatal mistakes. Having room for error allows compounding and good decisions to keep working over time.

Survival Enables Long-Term Success

Endurance is impossible without slack. Those who leave space for mistakes stay in the game long enough to benefit from long-term trends and opportunities.

Why should the reader care?

Because a lack of margin turns small problems into life-altering failures.

Mental Model

Margin of safety equals staying power.

Key Insights

- No plan works perfectly in the real world

- Small mistakes can cause major damage without buffers

- Room for error reduces emotional stress

- Survival matters more than optimization

Common Mistake to Avoid

Building plans that work only under ideal conditions and collapse under stress.

Designing for Survival (Practical Principle)

Plan for what can go wrong, not just for what you hope will go right. Conservatism protects long-term freedom.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Build emergency funds beyond minimum requirements

- Reduce leverage that magnifies small losses

- Make conservative assumptions in planning

- Leave flexibility in commitments and timelines

Chapter in One Sentence

Room for error is what keeps good plans alive when reality intervenes.

14: You’ll Change

“Long-term planning is harder than it seems because people’s goals and desires change over time.”

The biggest risk in long-term planning is assuming you’ll stay the same person.

Chapter Summary

Why We Overestimate How Stable We Are

This chapter explores a quiet but powerful truth: people change more than they expect. Tastes, values, ambitions, and priorities evolve with age, experience, and circumstances. Yet when making long-term financial plans, people often assume their future selves will want the same things they want today.

Housel explains that this mismatch creates regret. A decision that felt perfect at 25 can feel restrictive at 40. Careers that once felt exciting may later feel exhausting. Financial commitments made confidently can become emotional burdens when life changes.

Rigid Plans Create Future Frustration

Problems arise when plans are too rigid. Long-term commitments—large debts, inflexible careers, irreversible financial choices—limit the ability to adapt. When people change but their plans don’t, dissatisfaction grows.

Housel argues that many people mistake confidence for accuracy. Feeling certain today does not mean you will feel the same way later.

Flexibility Reduces Regret

The solution is not to avoid planning, but to plan with humility. Flexible plans acknowledge that change is inevitable. They leave room for new interests, different goals, and unexpected opportunities. This flexibility reduces regret and increases long-term satisfaction.

Why should the reader care?

Because plans that don’t allow change often become sources of stress and regret.

Mental Model

Plan for change, not permanence.

Key Insights

- People change more than they expect

- Long-term certainty is often an illusion

- Rigid plans increase future regret

- Flexibility improves long-term happiness

Common Mistake to Avoid

Making irreversible financial decisions based on who you are today, not who you might become.

Building Plans That Age Well (Practical Principle)

Design financial and life plans that allow adjustment. The ability to change direction is a form of protection.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Avoid commitments that lock you into one path

- Leave financial and career options open when possible

- Revisit long-term plans regularly

- Value adaptability over optimization

Chapter in One Sentence

The best long-term plans are flexible enough to evolve as you do.

15: Nothing’s Free

“Everything has a price, but not all prices appear on labels.”

Every reward comes with a cost—and the most important costs are emotional, not financial.

Chapter Summary

Why Every Financial Gain Has a Hidden Cost

This chapter focuses on an uncomfortable truth people prefer to ignore: there are no free rewards in finance. Higher returns always come with trade-offs. These costs are rarely obvious and are often paid in forms people don’t expect—stress, volatility, uncertainty, and discomfort.

Housel explains that many people want the rewards of investing without accepting the emotional price that comes with it. They want high returns but panic during downturns. They want growth but feel betrayed when markets fall. The problem is not the market—it is misunderstanding the cost of participation.

Volatility Is the Admission Fee

Market volatility is not a flaw. It is the price of admission. Just like paying a ticket to enter a theater, investors must accept swings and uncertainty to earn long-term returns. Those who view volatility as a fine instead of a fee are more likely to quit at the wrong time.

Understanding this reframes discomfort. Instead of seeing volatility as a mistake, it becomes a necessary expense for progress.

Accepting the Price Changes Behavior

Once people accept that discomfort is part of the deal, they make better decisions. They stop chasing unrealistic stability and start building strategies they can tolerate emotionally. Paying the price willingly is what separates long-term success from short-term regret.

Why should the reader care?

Because avoiding the emotional cost of investing guarantees poor long-term results.

Mental Model

Volatility is the fee for long-term rewards.

Key Insights

- All financial rewards come with hidden costs

- Volatility is not a punishment—it’s the price

- Wanting returns without discomfort leads to bad decisions

- Accepting the cost improves long-term behavior

Common Mistake to Avoid

Treating market volatility as a mistake rather than as the cost of earning returns.

Paying the Price Willingly (Practical Principle)

Before pursuing any financial goal, ask whether you are willing to pay its emotional and psychological cost. If not, adjust the goal.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Reframe volatility as a normal part of investing

- Stop expecting steady returns in uncertain markets

- Choose strategies whose emotional cost you can tolerate

- Stay invested by accepting discomfort upfront

Chapter in One Sentence

Every financial reward has a price, and volatility is the cost of long-term success.

16: You & Me

“Incentives are the most powerful force in the world.”

People don’t act based on what is right—they act based on what benefits them.

Chapter Summary

Why Behavior Follows Incentives, Not Logic

This chapter explains that human behavior is driven less by intelligence or morality and more by incentives. People respond to rewards, penalties, recognition, and personal benefit. When incentives are misaligned, even smart and well-intentioned people make poor decisions.

Housel shows that many financial outcomes—booms, crashes, bubbles, and scandals—can be traced back to incentives that encouraged risky or short-term behavior. When people are rewarded for taking risks without bearing the full consequences, they take more risks. This applies to individuals, companies, and entire financial systems.

Understanding Motives Improves Judgment

Instead of asking why someone made a bad decision, Housel suggests asking what incentive made that decision attractive. Once incentives are understood, behavior becomes predictable—even when it seems irrational.

This insight shifts how we judge others and ourselves. Poor outcomes are often not caused by ignorance, but by incentives that encourage dangerous behavior.

Aligning Incentives Protects Long-Term Outcomes

Good financial systems—and good personal decisions—align rewards with long-term consequences. When incentives reward patience and responsibility, behavior improves naturally.

Why should the reader care?

Because misunderstanding incentives leads to repeating the same costly mistakes.

Mental Model

Behavior follows incentives, not intentions.

Key Insights

- People respond to incentives more than logic

- Bad incentives produce bad outcomes, even with smart people

- Understanding motives explains seemingly irrational behavior

- Long-term success depends on aligned incentives

Common Mistake to Avoid

Assuming people act irrationally without examining what rewards or pressures they face.

Designing Better Incentives (Practical Principle)

When making financial decisions, ask what behavior your incentives encourage. Adjust systems so rewards support long-term stability, not short-term gain.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Examine incentives behind your financial decisions

- Avoid systems that reward short-term wins over durability

- Align personal goals with long-term consequences

- Judge behavior by incentives, not outcomes alone

Chapter in One Sentence

People behave according to incentives, not intelligence or intention.

17: The Seduction of Pessimism

“Optimism sounds naive. Pessimism sounds smart.”

Bad news spreads faster not because it is more accurate, but because it feels more convincing.

Chapter Summary

Why Bad News Feels Smarter Than Good News

This chapter explains why people are naturally drawn to pessimism. Negative stories sound serious, intelligent, and realistic. They demand attention and create a sense of urgency. Optimistic stories, on the other hand, are often dismissed as naive or overly hopeful—even when they are supported by long-term data.

Housel points out that progress usually happens slowly and quietly, while setbacks happen suddenly and loudly. A market crash grabs headlines. Steady growth rarely does. This imbalance makes pessimism feel more truthful, even when it misrepresents reality.

Fear Is More Persuasive Than Facts

Humans are wired to pay more attention to threats than to opportunity. This bias helped our ancestors survive, but it distorts modern financial thinking. When fear dominates, people overestimate risks and underestimate long-term growth.

Media, predictions, and financial commentary often amplify this effect. Dramatic negative stories attract more attention than calm explanations of gradual improvement. Over time, this creates a worldview where disaster feels inevitable, even when evidence suggests otherwise.

Long-Term Progress Is Easy to Miss

Housel emphasizes that optimism is not blind faith. It is trust in long-term progress despite short-term setbacks. History shows that economies grow, innovation continues, and living standards improve—but only if people stay invested long enough to benefit.

Pessimism feels protective, but it often leads to inaction, fear, and missed opportunities.

Why should the reader care?

Because fear-driven thinking can keep you out of opportunities that create long-term success.

Mental Model

Fear is loud; progress is quiet.

Key Insights

- Bad news feels smarter than good news

- Fear spreads faster than optimism

- Short-term pain hides long-term progress

- Pessimism often leads to poor decisions

Common Mistake to Avoid

Assuming that negative headlines reflect the long-term reality of markets or life.

Learning to See Progress Clearly (Practical Principle)

Separate short-term noise from long-term trends. Good decisions are made by those who can tolerate temporary discomfort while trusting gradual progress.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Limit exposure to fear-driven financial media

- Study long-term data instead of short-term headlines

- Remind yourself that volatility is not failure

- Stay invested despite uncomfortable news cycles

Chapter in One Sentence

Pessimism feels intelligent, but optimism is what benefits from long-term progress.

18: When You’ll Believe Anything

“Stories are more powerful than statistics.”

When facts are confusing, the mind reaches for stories that feel believable—even if they aren’t true.

Chapter Summary

Why Stories Feel Safer Than Numbers

This chapter explains how humans naturally prefer stories over data. Numbers are abstract and uncertain, while stories give simple explanations with clear causes and effects. When something complex or frightening happens—like a market crash or economic crisis—people instinctively look for narratives that explain why it happened and what will happen next.

Housel argues that this desire for storytelling is emotional, not intellectual. Stories provide comfort. They make chaos feel understandable and give people a sense of control, even when that control is an illusion.

How Believable Stories Distort Reality

The danger is that the most believable stories are often the least accurate. Simple narratives ignore randomness, luck, and complexity. They turn uncertain events into confident explanations. Over time, these stories shape decisions, push people toward extreme actions, and create false certainty.

Housel shows that financial bubbles, panics, and bad decisions are often driven by compelling stories rather than solid evidence. When fear or excitement is strong enough, people stop questioning whether a story is true—they only ask whether it feels right.

Learning to Be Skeptical of Certainty

The lesson is not to reject stories entirely, but to be cautious when explanations sound too clean or confident. In complex systems like markets and economies, uncertainty is normal. Anyone claiming complete certainty is likely oversimplifying reality.

Why should the reader care?

Because believable stories can push you into decisions that ignore risk and reality.

Mental Model

Compelling stories often replace uncomfortable truth.

Key Insights

- Humans prefer stories to statistics

- Simple explanations often hide complexity

- Certainty is emotionally appealing but dangerous

- Many financial mistakes begin with believable narratives

Common Mistake to Avoid

Trusting confident stories that explain complex outcomes too neatly.

Thinking Clearly in an Uncertain World (Practical Principle)

When a story feels too certain or emotionally satisfying, pause. Ask what uncertainties or unknowns are being ignored.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Be skeptical of predictions that sound overly confident

- Look for data behind popular financial narratives

- Accept uncertainty instead of chasing certainty

- Avoid decisions driven purely by fear or excitement

Chapter in One Sentence

Believable stories often feel true, even when they ignore reality.

19: All Together Now

“Good money behavior is more about what you do consistently than what you do occasionally.”

Financial success is not built from one big decision, but from many small behaviors repeated over time.

Chapter Summary

Why Simple Behaviors Matter More Than Big Moves

This chapter brings together the book’s core ideas and shows that successful money management is not about brilliance or complexity. It is about combining a few simple behaviors—patience, humility, saving, risk control, and long-term thinking—and practicing them consistently.

Housel explains that most people search for a single powerful strategy that will solve everything. In reality, success comes from avoiding obvious mistakes, staying flexible, and letting time do the heavy lifting. Small, reasonable actions repeated for years often outperform bold, complicated plans that are hard to maintain.

The Power of Consistency Over Intelligence

Intelligence and technical knowledge matter far less than behavior. You don’t need to predict markets, find perfect investments, or time decisions precisely. You need habits you can stick with through boredom, fear, and uncertainty.

This chapter emphasizes that good financial behavior looks boring from the outside. It rarely makes headlines. But over decades, it quietly produces stability and freedom.

Simplicity Reduces Mistakes

Complex strategies increase the chance of failure. Simple rules reduce emotional decisions and help people stay disciplined during stressful periods.

Why should the reader care?

Because long-term success comes from steady behavior, not dramatic moves.

Mental Model

Small habits, practiced consistently, create big outcomes.

Key Insights

- Financial success comes from behavior, not intelligence

- Consistency beats occasional brilliance

- Simple strategies reduce costly mistakes

- Long-term thinking compounds results

Common Mistake to Avoid

Chasing complex strategies instead of mastering basic, repeatable behaviors.

Building a Sustainable Money System (Practical Principle)

Create simple rules you can follow in good times and bad. A system that survives stress will outperform one that looks impressive on paper.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Simplify financial rules and strategies

- Focus on habits you can maintain for decades

- Avoid unnecessary complexity

- Judge progress over long periods, not short bursts

Chapter in One Sentence

Wealth is built by doing simple things consistently over a long time.

20: Confessions

“The hardest financial decisions are not about spreadsheets. They are about how you behave.”

There is no single right way to manage money—only ways that work for you.

Chapter Summary

Why Personal Rules Matter More Than Universal Advice

In this final chapter, Housel steps away from theory and shares his own financial beliefs. He does not present them as rules others must follow, but as examples of how personal values shape money decisions. The message is clear: finance is deeply individual. What works for one person may fail for another, even if both are intelligent and informed.

Housel emphasizes that financial success is not about finding the smartest strategy. It is about understanding yourself—your fears, goals, patience, and tolerance for uncertainty—and building rules that align with who you are.

Self-Awareness Is a Financial Skill

Many people fail with money not because they lack knowledge, but because they follow advice that clashes with their personality. Someone who cannot tolerate volatility should not chase aggressive returns. Someone who values freedom should not lock themselves into rigid obligations.

By accepting your limits instead of fighting them, you make better decisions and avoid regret.

The Goal Is to Be Reasonable, Not Perfect

Housel reinforces one final idea: the purpose of money is not to maximize returns, but to support a life you don’t want to escape from. Reasonable behavior—saving, patience, flexibility, and humility—wins because it is sustainable.

Why should the reader care?

Because understanding yourself leads to better decisions than copying “perfect” advice.

Mental Model

Self-awareness beats optimization.

Key Insights

- Money decisions are deeply personal

- There is no universal “best” strategy

- Self-knowledge prevents regret

- Reasonable behavior beats perfection

Common Mistake to Avoid

Blindly following financial advice that conflicts with your values or emotional limits.

Creating Your Own Money Rules (Practical Principle)

Define financial principles that reflect your goals, fears, and lifestyle. A plan that fits you will outperform one that looks smarter but feels wrong.

Action Steps You Can Apply Today

- Write down your personal money rules

- Identify risks you emotionally cannot tolerate

- Design strategies that support your desired lifestyle

- Measure success by peace of mind, not comparison

Chapter in One Sentence

The best money strategy is the one that fits who you are.

FAQ

What is The Psychology of Money about?

The book explains how behavior, emotions, and personal experience influence financial decisions more than intelligence or technical knowledge.

Is The Psychology of Money good for beginners?

Yes. It focuses on mindset and behavior, making it useful even for readers with no financial background.

Does the book teach investing strategies?

No. It teaches how to think about money, risk, saving, and decision-making rather than specific investment tactics.

What is the main lesson of the book?

Long-term financial success depends on patience, self-awareness, and avoiding destructive behavior—not chasing high returns.

Why does the book focus so much on psychology?

Because most financial mistakes are emotional, not mathematical. Understanding behavior leads to better outcomes.

Can this book help reduce financial stress?

Yes. It promotes flexibility, saving, realistic expectations, and long-term thinking—all of which reduce anxiety.

Is this book useful for entrepreneurs and professionals?

Absolutely. It helps with risk management, long-term planning, and decision-making under uncertainty.

What makes this book different from other finance books?

It avoids complex formulas and focuses on timeless human behavior that applies across cultures and income levels.